South Africa’s democratic crisis

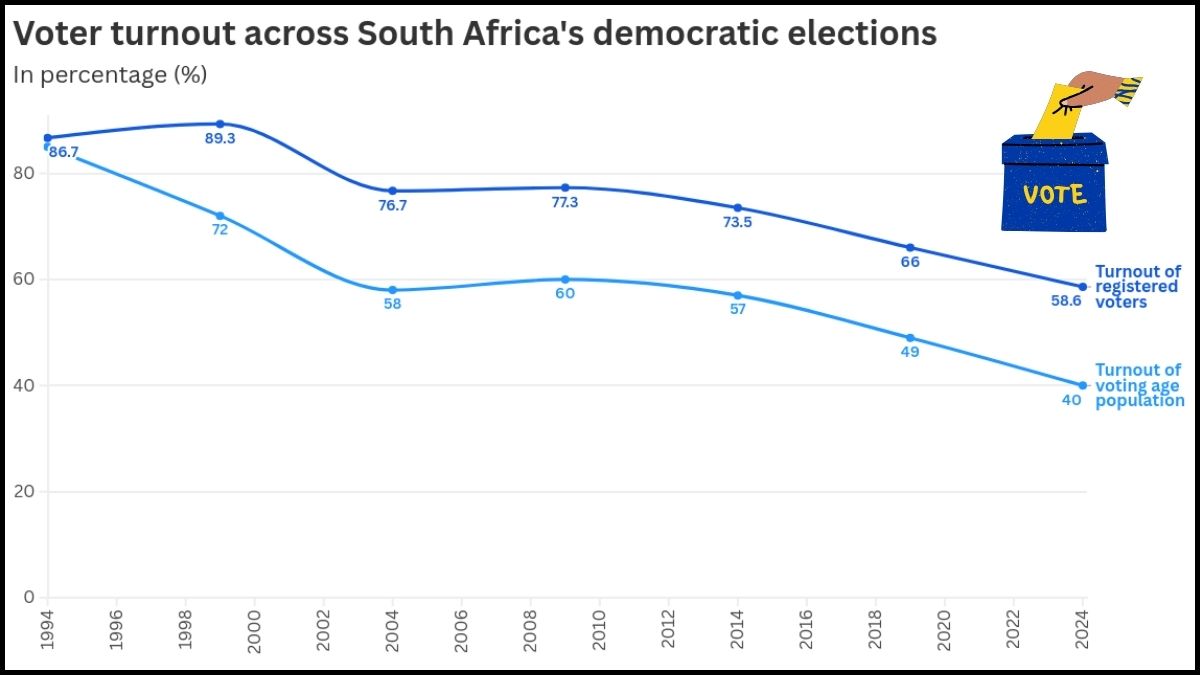

South Africa has experienced a steady and worrying decline in voter turnout since the dawn of democracy in 1994, despite a growing population and rising voter registration figures.

While the number of registered voters has increased over the years, the proportion of eligible South Africans who actually cast their ballots has dropped sharply.

The most significant gap is not between those who register and those who vote, but between the country’s Voting Age Population (VAP), everyone legally eligible to vote, and the number of votes ultimately recorded.

Data from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), using the VAP turnout definition, shows that voter participation peaked in 1994 at 85.5%.

Turnout then steadily declined over successive elections, falling below 50% in 2019 and reaching a record low of 39.6% in 2024.

Between 1999 and 2024, South Africa’s VAP grew by about 76%, rising from 22.6 million to 39.8 million.

Yet the number of ballots cast increased by only 63,054 over the same period. In 1999, 16,228,462 votes were recorded, compared to 16,291,516 in 2024.

A pre-election survey conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) found that the most common reason young people cited for not voting was dissatisfaction with government performance, particularly in tackling poverty, unemployment and corruption.

Globally, voter registration is compulsory in more than half of the 230 countries tracked by the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. In other states, registration is voluntary, with some countries automatically enrolling eligible citizens.

India, the world’s largest democracy, is among those that maintain voter rolls through automatic processes.

South Africa falls into the category of countries where voter registration is voluntary, and where citizens can register both online and in person, reducing logistical barriers to participation.

Analysis

Despite declining turnout, the country recorded its highest-ever number of registered voters in 2024, with 27.8 million South Africans signing up to vote.

Public Affairs Research Institute executive director Sithembile Mbete attributes this surge to an intensified registration campaign by the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), launched in response to poor voter turnout during the 2021 local government elections.

Mbete made the observation in a paper titled Making sense of voter turnout in the 2024 South African National and Provincial Elections, published in the Journal of African Elections in 2024.

The IEC boosted registration through social media campaigns and partnerships with civil society organisations, focusing particularly on first-time voters under the age of 30.

The strategy produced some results, with the IEC reporting that 77% of new registrations came from people aged 19 to 29.

This group is also the country’s largest VAP cohort, numbering more than 11 million in 2024, according to the study.

However, the IEC’s outreach did not translate into broad youth participation. Only about half of South Africans under 30 registered to vote.

By contrast, registration rates were significantly higher among older voters: 67% for those aged 30 to 39, 79% for those aged 40 to 49, 90% for the 50 to 59 group, and 93% for those aged 60 to 69.

A similar pattern emerged in voter turnout figures, using the IEC definition. Voters aged 18 to 29 recorded the lowest turnout, while those aged 70 to 79 recorded the highest.

Mbete points to generational voting theory — the idea that people become more politically engaged as they age — as one explanation for the trend.

However, she argues that South Africa’s persistently high youth unemployment levels may also play a role, as many young people are unable to reach “traditional markers of adulthood” often associated with higher electoral participation.

The Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) said South Africa does not face a crisis of democracy itself, but rather a crisis of democratic governance driven by political instability.

It argued that politics in the country has become defined by abnormal competition for power at any cost, resulting in shifting alliances, weak ideological grounding, and increasing factionalism.

EISA noted that this has fuelled party fragmentation, with several breakaway parties emerging from both the ANC and DA, often following disciplinary action or expulsions.

EISA added that while the legitimacy of political parties and democratic institutions is largely intact, their credibility has steadily eroded.

It said political parties have become increasingly disconnected from society, more focused on internal power struggles and patronage than public needs, contributing to a growing crisis of representation and accountability.