Relief for South African cattle farmers on the way

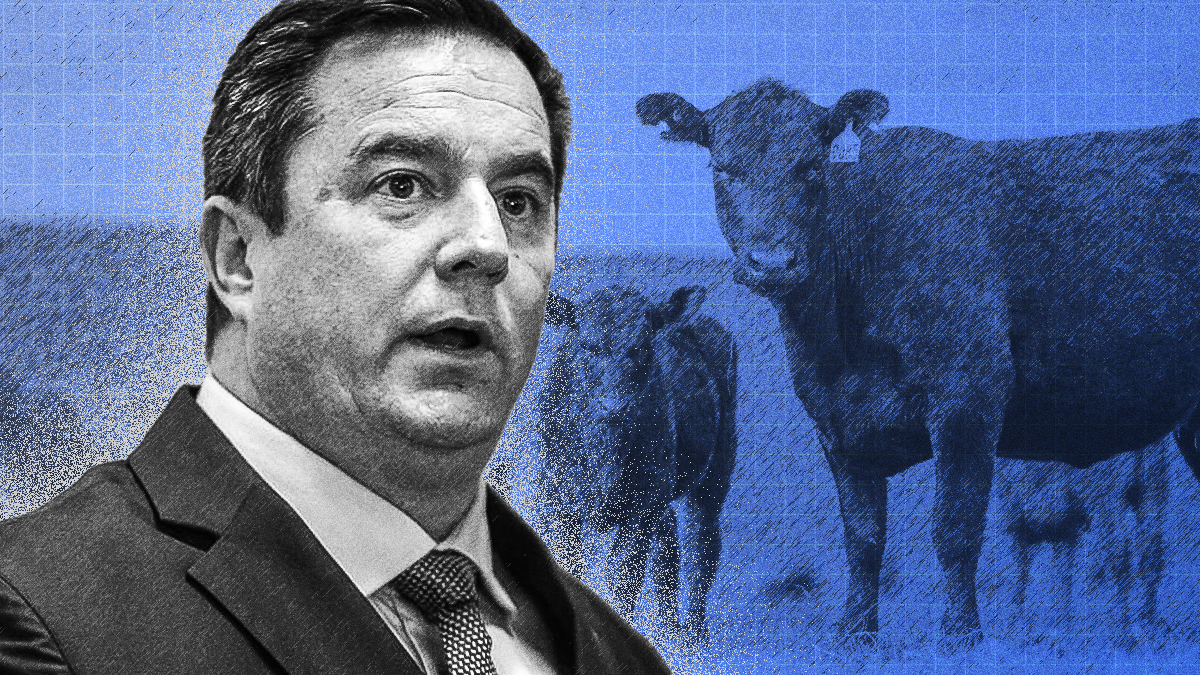

Agriculture Minister John Steenhuisen has announced that the first batch of one million foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) vaccines will arrive in South Africa on Saturday, 21 February 2026.

The shipment from Biogénesis Baġo in Argentina is the first phase of a broader agreement. A further five million doses are set to follow in March.

In addition to the Argentine supply, the Botswana Vaccine Institute (BVI) remains a vital partner.

It has delivered two million doses since the recent outbreak and is scheduled to provide FMD vaccine doses on a monthly basis.

“This vaccination rollout marks the beginning of restoring stability to the livestock sector and rebuilding confidence in our animal-health system,” said Steenhuisen.

In 2025, Steenhuisen called on the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) to fast-track the production of locally produced vaccines.

The vaccine, which hasn’t been produced in over 20 years, can protect livestock for up to 12 months.

On 6 February 2026, the ARC handed over the first batch of 12,000 vaccines to Steenhuisen.

The ARC have voiced its commitment to produce 20,000 vaccines per week. Further plans to scale up to 200,000 per week in 2027 were announced.

Despite this recent breakthrough, the Department of Agriculture has faced criticism from industry experts.

Southern African Agricultural Initiative (SAAI) chairperson Dr Theo de Jager argued that the government’s delay in action has created a bottleneck in vaccine administration.

He attributes the rapid spread of FMD to the government, specifically the Department of Agriculture’s delayed response.

SAAI first identified the outbreak in November 2024, reporting a spike in cases. The government was alerted but only declared the affected areas in March 2025.

De Jager described the delayed response as “allowing a wildfire to run for five months until you decide to send water”.

The government has officially classified the spiralling FMD outbreak as a national disaster, effective 13 February 2026.

Head of the National Disaster Management Centre, Dr Elias Sithole, gazetted the classification under Section 23 of the Disaster Management Act.

While the Animal Diseases Act remains the primary legal framework under Section 23, the formal classification is significant.

It acknowledges the sheer scale of the crisis and, critically, mandates a coordinated response from government at all levels and from the private sector.

The classification follows a high-stakes meeting on Monday, 9 February, that involved President Cyril Ramaphosa, Steenhuisen, and industry leaders.

During the meeting, the President pledged improved cooperation between the government and the agricultural community.

Using available resources

The government initially prohibited private vets from administering FMD vaccines. De Jager claims that this state control and vaccine monopoly exacerbate the FMD crisis.

Dr Frikkie Maré of the Red Meat Producers’ Organisation (RPO) corroborated this legal gridlock.

He warned that farmers can’t buy private vaccines because the necessary permissions have not yet been gazetted.

De Jager noted that the state lacks veterinarians, vehicle networks, and logistics to vaccinate the entire national herd of 14 million cattle.

Some farmers agree with De Jager’s opinion. A recent SAAI poll with more than 2,000 participants shows low confidence in the government’s ability to resolve the crisis.

Approximately 95% of respondents feel the FMD response was too slow, the vaccine rollout was poorly managed, and experts were silenced, and 87% believe that leadership has failed.

During the State of the Nation Address debate on 17 February, Steenhuisen announced that, under the Animal Disease Act (ADA), private veterinarians can register to administer vaccines.

“In these tough times, we all need to be working together. Every South African’s support is vital to help our farmers win this war against FMD,” Steenhuisen said.

Prior the the announcement, the private agricultural sector was pursuing a court order to interpret the ADA in their favour and gain the right to vaccinate.

He further explained that expanded manpower will help ensure the department meets its vaccination target of 80% of the national herd by December 2026.

Despite the government’s efforts, the disease continues to decimate the industry. The Department of Agriculture’s data further confirms the “wildfire” spread as described by De Jager.

As of mid-February 2026, the department has recorded 836 open outbreaks. The Free State is the epicentre with 245 open outbreaks.

KwaZulu-Natal has 202 open outbreaks, and approximately three dairy farms are destroyed every day.

The department’s data show that in KwaZulu-Natal, “complete resolution of this event is unlikely” because the disease is manifesting in buffalo populations in game reserves.

FMD poses a severe multi-billion-rand threat to South Africa’s future, risking the collapse of the agricultural export market, significant job losses, and worsening economic instability.

“Our farmers are the providers of our food and the backbone of our economy, bringing essential foreign currency into the country,” Steenhuisen said.

To better support our farming community, the department has established a dedicated FMD Control Centre. Starting this Wednesday, farmers can access a toll-free support line for expert guidance on FMD.

This article was written by Zané Steyn.