South African security nowhere near government’s 2030 utopia

With a murder rate that has consistently increased over the past decade and an allegedly captured police force, security in South Africa today is far from what the country envisaged for the year 2030.

In its 2012 National Development Plan (NDP), the the National Planning Commission (NPC), chaired by Trevor Manuel, outlined the state of the country it envisaged by 2030.

The nearly 500-page document covered everything from improving education to fighting corruption and positioning the country in the greater global context.

The document included “building safer communities,” which aims to increase public safety by improving policing, strengthening the criminal justice system, and focusing on the protection of women and children.

The country’s vision for this, as outlined in the document, was that by 2030, “people in South Africa feel safe at home, at school, and work, and they enjoy a community life free of fear.”

“Women walk freely in the streets and children play safely outside,” it continues.

“The police service is well-resourced and professional, staffed by highly skilled officers who value their work, serve the community, safeguard lives and property without discrimination, protect the peaceful against violence, and respect the rights to equality and justice.”

However, as the NPC, which performed a ten-year review of the NDP, pointed out, the country is not only off track to meet many of its goals, but is also moving in the wrong direction.

As for the security of those living in the country, the NPC noted that “South Africans experience some of the highest levels of violent interpersonal crime globally, especially violence against women.”

For starters, South African cities consistently rank in the top twenty most dangerous cities in the world based on the number of murders per 100,000 people.

According to Igarape Institute, a public and digital security thin tank, five South African cities ranked in the top twenty globally by murder rate between 2020 and 2023.

These were Nelson Mandela Bay (2), Durban (9), Cape Town (16), Pietermaritzburg (17), and Buffalo City (19).

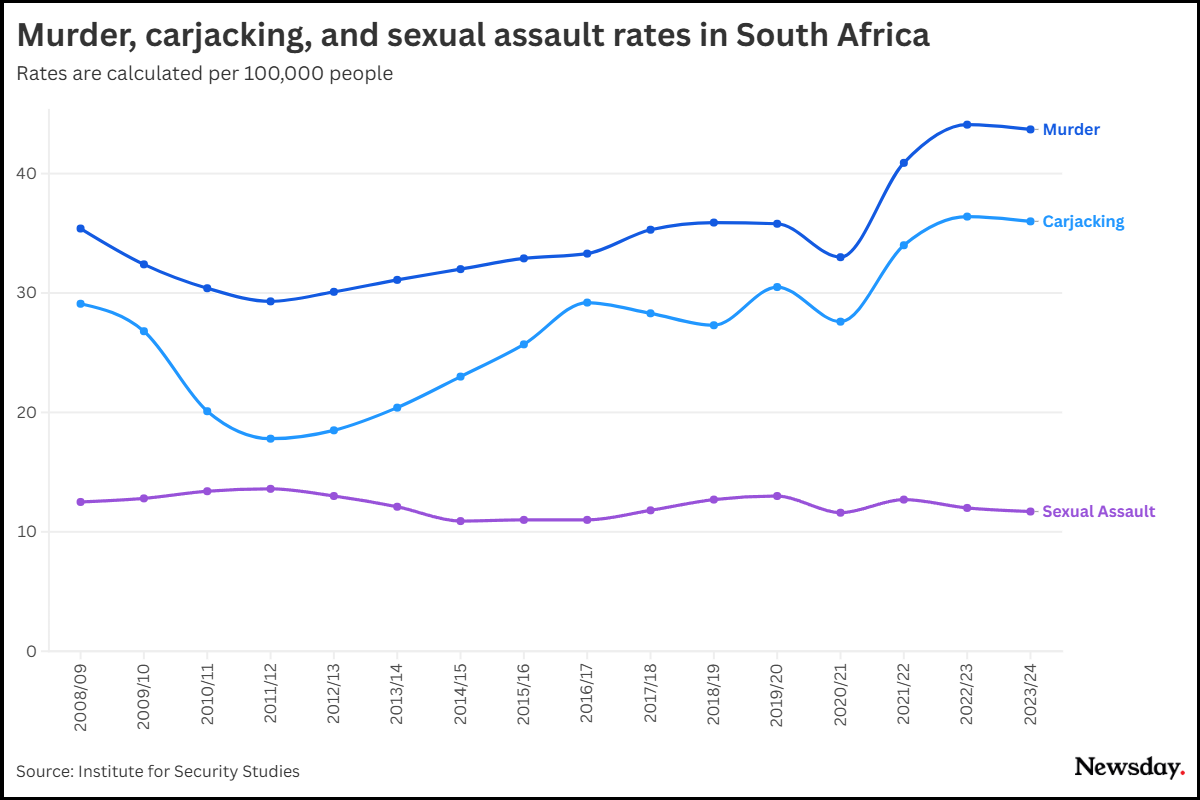

Looking at the murder rate for South Africa as a whole, the Institute for Security Studies notes how this figure decreased by more than half between 1994/95 and 2011/12, from 69 to 29.5.

However, since then, it has consistently increased every year except for the 2020/21 financial year.

This period saw the total number of murders committed in the country increase by over 12,000 from 15,554 to 27,621.

Similarly, other serious crimes, such as sexual assault and rape, which women and children are often the victims of, have also failed to see any sign of a significant decline over time.

For instance, the number of sexual assault cases reported to the police since 2007/08 has fluctuated between 6,000 and 8,000 per year, but has not dropped below this range.

Since 2014/15, the number of cases reported to the police has increased from 6,087 to 7,418 in 2023/24.

Cases of rape reported to the police over the same period decreased from 46,647 to 42,569. However, this declined by just under 10% over roughly 15 years.

Carjacking, which is another major crime in South Africa, followed a similar trend to the murder cases, reaching a low of 9,417 in 2012/13 and more than doubling to 22,735 by 2023/24.

It is critical to note that these figures are not an accurate reflection of the rate of crime in the country, as the consistent decline in trust in the South African Police Service (SAPS) has meant that less people have been reporting crimes.

The Human Sciences Research Council’s round 21 of the South African Social Attitudes Survey showed that only 22% of citizens expressed trust in the SAPS.

An eroding police force

Independent researcher David Bruce says that it is the view of many analysts that an increase in organised crime is behind the rise in murders in South Africa.

He points to three arguments as to why this may be the case. The first is the erosion of policing independence in South Africa, which is evident in the number of cases solved.

The second is the release of state guns to the criminal underworld, and the third is the increase in the number of gun licences issued.

The effect of the erosion of South Africa’s police has recently come to light, following several allegations made by KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi.

These allegations included that the SAPS has been “captured” by organised crime syndicates.

While the allegations are yet to be investigated, this highlights how South Africa is moving further away from its NDP goals of a safer country and “well-resourced and professional police force.”

In a report titled “Can the SAPS really keep us safe?”, the ISS argues that the police force’s size and complexity require that it operate according to sound principles.

“Its leadership and management structures and systems have, for more than 10 years, been unable to identify and effectively address multiple organisational shortcomings,” it says.

“There remains an absence of clear, practical plans for strengthening the efficiency and effectiveness of the SAPS.”

“Instead, reliance has been on the assumption that the SAPS’s ability to better tackle crime can be solved largely by adding more resources, particularly in the form of personnel.”

The training of police officers, or lack thereof, has been under scrutiny for some time. The country has paid out nearly R2 billion in five years for claims made against instances of police misconduct.

Civilians made these claims for wrongful arrests and detentions, as well as shooting incidents involving police officers.

Yet, this is only a fraction of the total amount in civilian claims to SAPS, which amounted to over R15 billion in 2023/24.