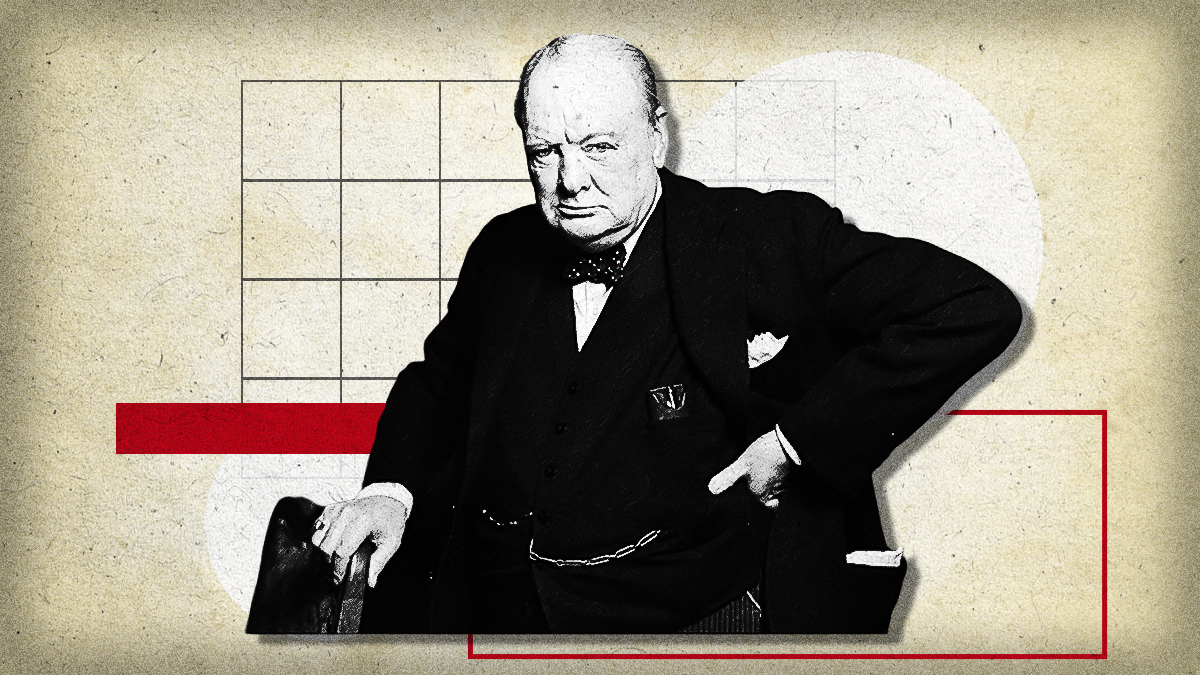

When a future British Prime Minister was a prisoner of war in South Africa

Before he was the “British Bulldog” who stood against Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, former Prime Minister Winston Churchill was a young, ambitious, and somewhat reckless war correspondent caught in the crossfire of the Second Anglo-Boer War.

While travelling on an armoured train through the rugged terrain of Natal, Churchill was captured by Boer commandos, an event that threatened to end his political ambitions before they had even begun.

In late 1899, the future British Prime Minister arrived in Cape Town, ostensibly as a war correspondent for The Morning Post.

His luggage reflected a man who intended to experience war with a degree of comfort, containing sixty bottles of spirits, twelve bottles of Rose’s Lime Juice, and a supply of claret.

However, within two weeks of his arrival, this would be replaced by the harsh reality of a prisoner of war camp, following a dramatic and chaotic ambush that would become known as the “Armoured Train Incident”.

By early November 1899, British forces in Natal were on the back foot, having retreated south of the Tugela River to Estcourt.

In what was described as a “phoney war,” the British relied on a specific, and deeply flawed, method of reconnaissance: the armoured train.

This contraption was comprised of open trucks encased in thick boiler plate walls seven feet high, hauled by a locomotive.

Officers in Estcourt viewed the train as an “oxymoron” for reconnaissance purposes; it was audible for miles due to the “grunting and puffing of the engine,” and visible from great distances, allowing Boer commandos ample time to prepare ambushes.

The train ran a predictable route through narrow valleys where visibility was limited to 800 yards, leading local soldiers to grimly nickname the vehicle “Wilson’s Death Trap”.

Despite the known dangers, a sortie was ordered for November 15, 1899.

The train carried a company of the Dublin Fusiliers, men from the Durban Light Infantry (DLI) under Captain J.S. Wylie, and a small detachment from HMS Tartar manning an antiquated 7-pounder gun.

Command fell to Captain Aylmer Haldane, who had only recently recovered from wounds sustained at the Battle of Elandslaagte.

Accompanying him in the armoured truck was the eager war correspondent, Winston Churchill.

The ambush

As outlined in the Times History of the War, the train departed Estcourt at approximately 5:30 a.m., proceeding cautiously toward Chieveley.

Upon arrival, they received reports of Boer movements and, observing enemy forces to the west, Captain Haldane immediately ordered a retreat back to Frere.

The Boers, however, had sprung their trap. As the train rounded a spur of a hill roughly two miles from Frere, Boer artillery opened fire from 600 yards.

The British engine driver, Charles Wagner, increased speed to escape the kill zone, but the enemy had prepared the line.

Theories differ on the exact nature of the obstruction, but the result was catastrophic for the British. Churchill later described a huge stone, while others suggested loosened bolts or removed fishplates.

The train, speeding to escape the shelling, smashed into the obstruction.

The leading truck was thrown into the air, landing upside down, while the armoured truck behind it was derailed onto its side, spilling its occupants and crushing others.

The third truck wedged itself across the track, effectively trapping the engine and the remaining carriages behind it.

Churchill’s “martial ascent”

It was in this chaotic moment that the journalist shed his observer status and took command of the situation.

While Captain Haldane attempted to keep the enemy’s head down with rifle fire, Churchill volunteered to clear the line.

For the next seventy minutes, under a “storm of small arms fire” and artillery shelling, Churchill worked to free the engine.

He found the driver, Wagner, wounded by a splinter and ready to abandon the train. In a display of the leadership that would later define his career, Churchill rallied the man, telling him that “it was impossible to be hit twice on the same day”.

With Churchill directing operations, the engine was used to ram the partially derailed truck repeatedly.

It was a brutal, grinding process carried out while Boer shells exploded around them—one striking the footplate near Churchill’s head and another smashing the arm of a Dublin Fusilier standing nearby.

Eventually, the engine managed to squeeze past the wreckage, but the trucks behind it remained stranded.

The surrender

Realising the rear trucks could not be saved, Haldane ordered the engine to ferry the wounded to safety while the remaining infantry fought a rearguard action back to some houses near Frere.

Churchill, who had been on the locomotive, made a fateful decision. Instead of escaping to safety on the engine, he jumped off to return to the infantry.

By the time he returned, the infantry had been scattered. As he moved through a railway cutting, he found himself cornered by two Boers.

He scrambled up a bank attempting to escape, only to find a mounted Boer waiting forty yards away.

This horseman is alleged to have been Sarel Oosthuizen, known as the “Red Bull of Krugersdorp”. Facing a rifle and realising escape was impossible, Churchill surrendered.

The aftermath was grim. The British suffered significant casualties, with official records listing 5 killed and 47 wounded, though accounts vary.

The survivors, including Churchill, were forced to march through the rain and mud, described by a witness as a “little compact body of men… with a man in mufti with an injured hand among them”.

Legacy of the capture

Captain Wylie of the DLI later summarised the correspondent’s actions with blunt admiration: “He was a very brave man but a damned fool.”

Churchill was imprisoned at the State Model Schools in Pretoria.

However, his captivity was short-lived. On the night of December 12, he famously scaled the prison fence when the guards’ backs were turned, eventually making his way to freedom via Delagoa Bay.

The incident on the armoured train did more than just provide copy for The Morning Post; it established Churchill’s reputation.

He returned to England a hero, leveraging his newfound fame to win a seat in Parliament in the 1906 general election, setting him on the path to the Premiership.

In 1910, as Home Secretary, he ensured that the driver, Charles Wagner, and his fireman received the Albert Medal, the highest award for gallantry available to civilians, acknowledging that dirty overalls were “nothing compared to what he and I went through together”.