Inside the South African informal settlement terrorised by Zama Zamas

On the periphery of the decaying Krugersdorp Central Business District, nestled near a river canal and old abandoned mine shafts, lies “Plastic View.”

It is a mushrooming informal settlement that serves as a stark microcosm of South Africa’s dual reality: the desperate, industrious drive for self-sufficiency and the paralysing fear of violent crime.

For the waste pickers who have called this place home for decades, life is a daily negotiation between earning a living through recycling and surviving the terror inflicted by illegal miners, known as Zama Zamas.

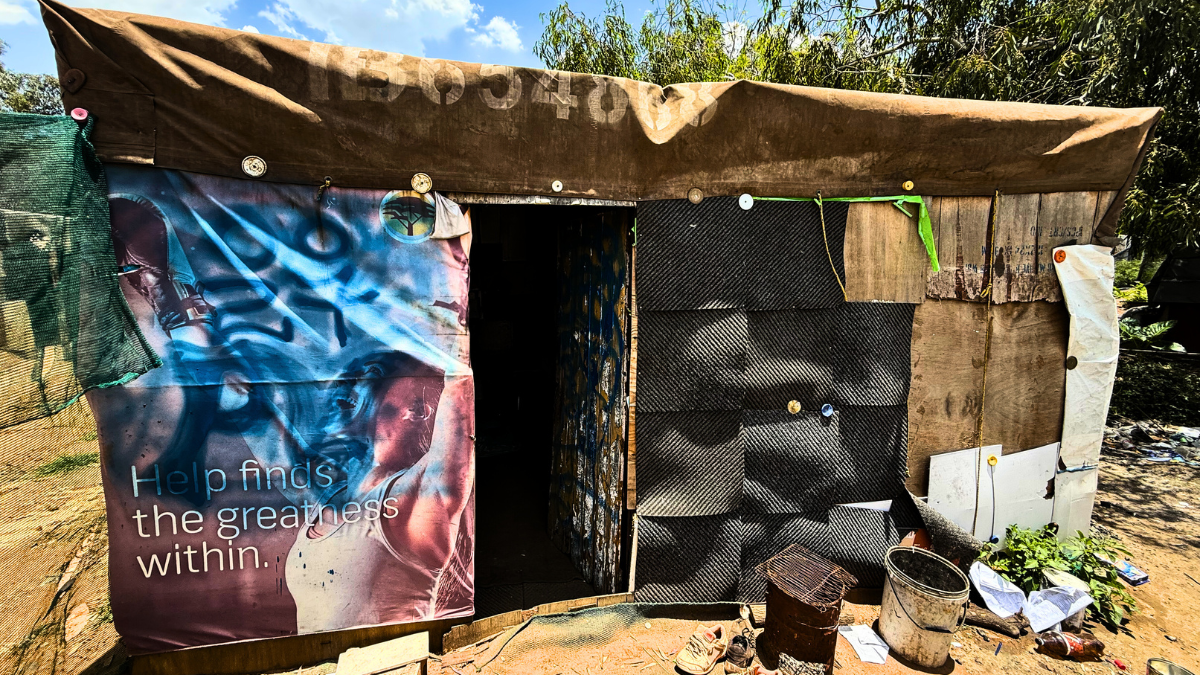

To the outsider, Plastic View appears as a chaotic cluster of shacks built from scavenged materials, living in what observers describe as “absolute destitution.”

However, inside the community, there is a structured, self-regulated economy.

Jack, a community leader and resident since 2008, told Newsday that the residents are not looking for handouts.

“We don’t go around carrying placards and say we want jobs… if you can do it yourself,” he explained.

The community subsists primarily on recycling, gathering materials from the town to sell.

They have organised their lives around this trade, building their own structures and managing their own survival with minimal government intervention.

Their vision for the future is one of entrepreneurial independence. Currently, they are forced to sell their goods to middlemen, recycling centres often owned by foreign nationals, who take a cut of the profits.

Jack’s goal is to formalise their operations: “We basically want to do it ourselves. Maybe we can have a big container… a generator where we can just operate our scale… we don’t want to sell to these people anymore.”

By bypassing the middlemen and selling directly to production companies, the community hopes to secure a sustainable income.

The municipality provides only a portion of their basic needs, such as sporadic water supply and chemical toilets, leaving the community to manage the rest themselves.

Despite the harsh conditions, where every shack leaks when it rains, the residents display a fierce pride in their ability to “make it work” without waiting for a government that has kept them waiting for years.

A community under siege

However, this industrious spirit is constantly threatened by the settlement’s dangerous geography.

Plastic View is located adjacent to abandoned mine shafts used by Zama Zamas. The proximity to these illegal mining operations has turned the settlement into a hunting ground.

Residents describe being “traumatised and always attacked” by the miners. The violence is brutal and pervasive.

Women in the community have been raped, and residents are frequently robbed of their meagre earnings.

The attacks often occur in the early hours of the morning, around 2:00 AM or 4:00 AM, terrorising people as they sleep.

Compounding the trauma is a profound lack of protection. The community is afraid to report these crimes to the police.

The threat of retaliation silences victims, leaving them trapped in a cycle of violence with no recourse to the law.

Additionally, “these Zama Zamas are faceless as they are not from here. Nobody knows who they are. How do you track a ghost?” remarked another resident.

Municipality response

The Mogale City municipality said that it provides water tankers and sanitation services to the community, including Jojo tanks and two chemical toilets.

Spokesperson for the municipality, Adrian Amod, told Newsday that the Plastic View land was illegally occupied and is not suitable for permanent human settlement development.

“The municipality has previously attempted to conduct a social survey; however, officials were unable to proceed due to safety threats allegedly by occupiers.”

With regards to the Zama Zamas, Amod said that the municipality’s Public Safety Unit monitors the area and reports criminal incidents to SAPS.

There is a glimmer of hope on the horizon. Discussions are underway with the municipality and the Department of Human Settlements to relocate the community to a safer piece of land.

This new location would move them away from the river canal and, crucially, further from the Zama Zamas and the dangerous mine shafts.

Councillor Mark Trump notes that the community approached the municipality with this solution rather than waiting for officials to act.

“They’re not asking us to do much for them… they’re asking for the basic, basic of human rights services and support,” Trump notes.

For now, the people of Plastic View remain in limbo. They are a community that has built homes out of waste and an economy out of scraps, proving their resilience daily.

WATCH: Inside the Plastic View informal settlement

More images of Plastic View informal settlement