Tough questions for the DA on the FMD vaccine rollout in South Africa

South Africa is currently grappling with its worst Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) outbreak in recorded history.

It has been described by veterinary experts as a “tragedy” and a “crisis” affecting the entire agricultural value chain, from large commercial beef and dairy producers to communal farmers.

FMD is a severe, highly contagious viral disease of livestock that has a significant economic impact. The disease affects cattle, swine, sheep, goats and other cloven-hoofed ruminants.

The disease is characterised by fever and blister-like sores on the tongue and lips, in the mouth, on the teats and between the hooves.

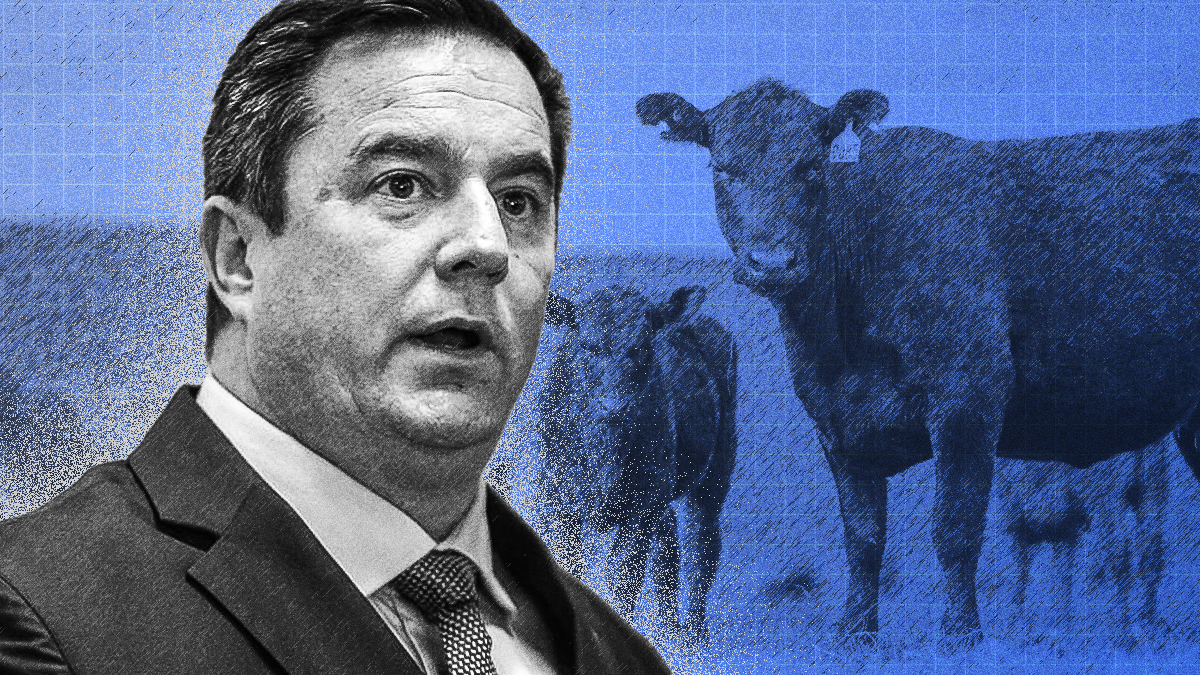

The Department of Agriculture, led by Minister John Steenhuisen, has announced a national strategy formulated by a Ministerial Task Team comprising scientists and veterinarians.

According to them, the ultimate objective is to regain the “FMD-free status with vaccination” from the World Organisation for Animal Health.

The Minister and Democratic Alliance leader said that achieving this status requires South Africa to prove there has been no virus transmission for at least 12 months.

He said that this is a standard that necessitates a strictly controlled vaccination rollout, official surveillance, and centralised monitoring – a process expected to take up to 10 years.

According to Steenhuisen, allowing a decentralised approach without state-led control would negate the strategy, as systematic coverage could not be verified for international trade purposes.

Given that years of maladministration led to the collapse of South Africa’s vaccine production capabilities, the state has been forced to acquire two million vaccines from the Botswana Vaccine Institute.

The department also said that it has begun issuing permits to private companies to import additional vaccines as local agents.

Despite these plans, the government faces significant legal challenges.

A coalition comprising Sakeliga, the Southern African Agri Institute (SAAI), and Free State Agriculture has launched litigation against the Minister to set aside the prohibition on private vaccinations.

These groups argue that the current outbreak is “severely out of control” and that the state’s centralised control is failing.

The legal challenge is rooted in the following arguments:

- Irrationality: The lobby groups contend it is irrational to prohibit livestock owners from protecting their herds when the state is failing to administer vaccines effectively.

- Legal Duty: They assert that Section 11 of the Animal Diseases Act obliges owners to take reasonable steps to prevent infection, and the current ban frustrates this legal duty.

- Capacity: The groups claim private sector participation would reduce the burden on the state and that ample vaccine supplies are available for import.

The Department of Agriculture said that this litigation poses a risk to the national strategy.

Steenhuisen described it as a push for a “vaccine free-for-all” as well as “short-sighted and reckless,” noting that technical responses to court challenges divert critical financial and veterinary resources away from the frontline fight against FMD.

The government maintains that without centralised oversight, the country risks “long-term damage.”

Conversely, the litigants argue that, facing “total operational collapse,” farmers cannot wait for a centralised bureaucracy that they view as failing.

While the state insists on a unified chain of command to manage the crisis effectively, agricultural interest groups believe the immediate survival of herds through private vaccination must take precedence.

The stance of Steenhuisen’s department has drawn further criticism from other parties, who argue that the state-controlled rollout is no different to if the African National Congress were to administer it.

Freedom Front Plus MP Dr Wynand Boshoff warned that government’s court battle to retain exclusive control over foot-and-mouth disease vaccines is deepening an economic crisis in rural communities.

Boshoff argued that while government may have funding, it lacks the capacity to manage vaccination alone and should welcome private-sector assistance.

The standoff has also reportedly caused internal friction within the DA.

For example, an editorial from the Common Sense suggests there is concern within DA ranks that Steenhuisen’s firm insistence on state control risks alienating the party’s core farming constituency.

Newsday’s questions for the Democratic Alliance on the FMD crisis:

Given that the Democratic Alliance purports to advocate for liberal economic policies, reduced government intervention and private sector-led growth for efficiency, as seen by one of its statements, “we do not believe that a state, with limited capacity, should over-reach itself”:

- How do you respond to criticisms that the roadmap for the FMD vaccine rollout fundamentally goes against these purported ideologies of the party by curbing the ability of private farmers to not wait on the government for help?

- Do you believe that the way the DA-led department is administering the vaccine rollout is any different from the way the ANC would? If so, how?

Answers from DA spokesperson Jan de Villiers:

The DA supports a whole of society approach, where the private sector, civil society and the state work together to reach the best outcomes for South Africans.

When Minister Steenhuisen took office and became aware of the pending FMD crisis, he immediately established the Biosecurity Council and convened a Bosberaad in Pretoria that brought together, for the very first time, the private sector, industry bodies, private veterinarians, state veterinarians, scientists, academics and agricultural organisations.

The outcome of that was the formation of a Ministerial Task Team, half of which was made up of private sector and industry veterinarians and the other half state veterinarians.

They were tasked with coming up with new strategies for us to deal with FMD and to advise the Minister on the best way forward.

Upon their advice, the Minister implemented the national proactive vaccination strategy, a similar model used by Brazil and Argentina to become FMD free.

In reaction to the state’s current inability to produce the required amount of vaccines, Minister Steenhuisen implemented a fast track emergency approval process through SAHPRA to import vaccines from other countries.

This has brought the private sector on board, and through private local agents we will soon have the Dollvet Vaccine (Turkey) and the Biogensys Bagò vaccine (Argentina) flowing into South Africa.

This will break the monopoly, lead to competition among suppliers and never again leave us reliant on a single supplier of vaccines.

This is a true liberal approach, where private and public actors coordinate and decide on a scientific and best use strategy for the best outcomes for South Africans.

For the very first time in our recent history, South Africa has a clear, science-based plan that will see us proactively dealing with FMD once and for all.

It is the DA’s belief that if the plan is executed efficiently and effectively, in partnership with the private and public sector, this will be the last major outbreak of foot and mouth disease in our country.

This will bring certainty to the livestock sector and will begin to open up the international market for our livestock and dairy farmers to markets that have been closed to us for decades.

How is it now DA Agric policy instead of government policy?

Your agenda is NOW so obvious.

Can you write an article about why some young prople elect to leave the Eastern Cape to go to other provinces for better prospects? How the ANC continues to misgovern and impoverish EC. How the deliberate underdevelopment and corruption in EC is creating a crisis in WC and Gauteng?