Julius Malema’s R1 billion headache

Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) Deputy President Godrich Gardee said the red berets spent R1 billion on campaigning for the 2024 national and provincial elections, raising eyebrows, as this is far from the funds the party actually declared.

Speaking at the EFF 2026 Plenum on 31 January 2026, Gardee said that South Africa’s democracy has become unaffordable, with political parties forced to spend unsustainable amounts of money just to compete.

He claimed the EFF alone spent about R1 billion on the 2024 national and provincial electionsand will have to spend more on the 2026 local government elections and the 2029 national polls.

“The EFF spent a billion rands in the 2024 elections alone,” Gardee said. “Two and a half years later, you are taking us to other elections, another R1 billion,” he added.

Gardee further argued that elections every two-and-a-half years create a funding crisis that drives corruption among political parties.

EFF president Julius Malema was quick to backtrack from Gardee’s comments, saying that the EFF did not spend R1 billion on the 2024 national and provincial elections and his comments were misunderstood.

“I said [to Gardee], why do you give an example of one billion? You must give examples of things you see with your own eyes. It was wrong.”

He stated that even if the party wanted to spend R1 billion, they do not have it and cannot get it, emphasising that “no one can ever give us R1 billion, not in South Africa.”

Malema argued that ‘monopoly capital’, big business, or wealthy interests refuse to fund or support the EFF due to its policies, challenging economic inequality and white monopoly capital dominance.’

The point, according to Malema, is that elections have been made expedient for the benefit of those who have money.

Regardless, this initial claim that the EFF spent R1 billion quickly raised eyebrows, particularly given that the party has only declared a fraction of that.

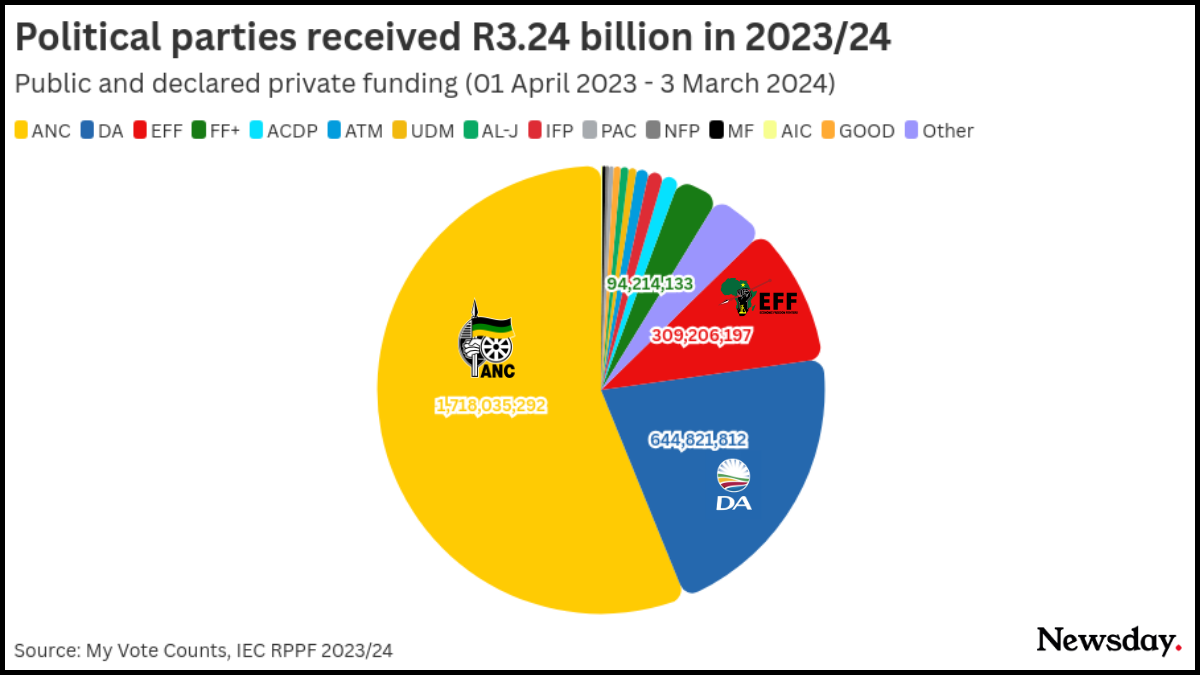

For example, according to the IEC’s party funding report for the 2023/24 financial year, the EFF received a combined total of R309,206,197 in public and private funding.

While much of the public funding is meant for the functioning of the representation of the EFF in the legislatures, the EFF declared just R50.73 million in private funding for that financial year leading up to the elections.

In response to the statement by Gardee, DA chairperson of the Federal Executive, Helen Zille, asked, “How much was declared to the IEC? Godrich is the Deputy President of the EFF, so he should know.”

“Was their billion Rand budget funded by R10 donations?” asked Zille.

ActionSA national chairperson Michael Beaumont told Newsday that “it is alarming that the remarks made by the EFF Deputy President clearly refer to a R1 billion spend in the 2024 elections against the backdrop of only declaring R51 million in donations.”

“ActionSA has raised serious concerns about political parties expending funds in a manner that cannot be substantiated by their declarations,” he added.

EFF’s funding and the question marks

Every year, the IEC publishes a detailed annual report of the known funding of political parties.

For the 2023/24 financial year leading up to the 2024 general elections, the IEC reported that the EFF sported a grand total of R309,206,197 – more than a third of the purported R1 billion campaign spend.

The majority of the EFF’s income came from state resources meant for the operations of legislative work. Public funding is divided into allocations from the IEC and legislative bodies.

The EFF received R179,614,725 from the National Assembly and provincial legislatures, and R78,859,537 disbursed by the IEC.

The funds disbursed by the IEC include money from the Represented Political Party Fund (RPPF) and the Multi-Party Democracy Fund (MPDF).

Looking at private funding, the EFF recorded R44,818,740 in membership fees and levies.

Notably, the EFF generated more revenue from membership fees than any other party, exceeding even the ANC in this specific category.

Of note, the party disclosed only R2,656,337 in private donations exceeding the R100,000 disclosure threshold.

Civil society organisation, My Vote Counts (MVC) noted that the EFF received approximately R1 billion from all its disclosed sources of income , private and public, for the three years 2021/22, 2022/23, 2023/24.

“We don’t yet have figures for what the party received in public funding since 1 March 2024 to date. For private funding from 1 March to now, it has disclosed very little,” noted MVC’s Joel Bregman.

Bregman said that for the party to have spent R1 billion on the 2024 elections raises questions, given their income and funding.

“Either they are overstating expenditure, or they have not been fully disclosing their private income and funding, or they are spending funds” that are from pre-party funding legislation days.

“Until we have a political funding framework that ensures transparency of all private income, as well as expenditure, it is impossible to verify such statements,” said Bregman.

“If the EFF’s claim is true, it would be easy for the party to prove it,” he added.

Could the IEC investigate this?

Until 2021, South Africa’s political funding system operated largely in secrecy, with no comprehensive legal framework regulating how political parties raised money.

This changed following a successful legal challenge by civil society organisations, led by MVC, which argued that the lack of transparency undermined democracy.

The Constitutional Court ruled that legislation was required to enhance transparency, inclusiveness, and accountability in political funding, addressing the public’s limited access to information.

This led to the enactment of the Political Party Funding Act (PPFA) in 2018, which came into force on April 1, 2021.

The law was later renamed the Political Funding Act (PFA) in 2024 to reflect broader electoral reforms.

The PFA introduced mandatory disclosure of private donations above R100,000, capped donations at R15 million per donor per year, created new public funding mechanisms, and banned donations from state-owned entities and foreign governments.

Amendments in August 2025 doubled the disclosure threshold to R200,000 and increased the annual donation cap to R30 million.

All registered political parties are required to submit annual audited financial statements to the IEC, detailing private donations, loans, membership fees, and allocations from public funds earmarked for specific purposes.

Collectively, this accounts for billions of rands flowing through the political system each year.

Despite this, concerns persist about the IEC’s ability to enforce compliance.

The Commission may only investigate complaints supported by evidence, cannot independently verify party submissions or loans, and faces budgetary constraints that limit enforcement.

MVC warns that enforcement remains the system’s weakest link. “Without real investigative capacity, noncompliance can flourish unchecked.”

Responding to previous questions from Newsday, the IEC said that “the Commission’s limitations are mainly with regard to limited internal investigation capabilities.”

While the IEC is empowered under Section 14 of the PFA to monitor compliance and demand documents, access premises, and question individuals about financial activities, much of the system relies on independent auditors, creating dependence on external verification.

The IEC can suspend public funding, recover irregularly spent money, impose administrative fines through the Electoral Court, and pursue criminal charges.

However, enforcement gaps remain stark. In the 2023/24 financial year, 510 of 581 unrepresented political parties failed to submit required income statements, without consequences.

“This flagrant noncompliance becomes particularly problematic in cases where unrepresented parties later win representation,” said MVC, as “the funding sources that backed their campaigns and helped boost their electoral prospects will remain unknown.”

By contrast, previously represented parties such as COPE, AIC, and NFP had their 2023/24 IEC funding withheld for noncompliance.

At a recent symposium hosted by MVC, SANEF, and the IEC, speakers warned of a “toothless” regulator.

While the IEC has prequalified legal and forensic experts and signed agreements with the Financial Intelligence Centre and the South African Reserve Bank, these have yet to be used.

Beaumont criticised the IEC’s approach, saying “the IEC has interpreted their role to only investigate when complainants effectively prove the allegations, which ActionSA submits is inadequate.”

“ActionSA has filed complaints against the ANC, EFF, and MK in this regard, but the IEC has failed to investigate these complaints.”

“They are given powers of investigation by the Act precisely because they can demand documents that a complainant cannot.”

The ActionSA chairperson said that “the IEC must fulfil its mandate by acting on complaints and not waiting for political parties to confess to breaches in the Act before they do anything.”

Can these red suited clowns get anything right? Lies and denying is their official language.